It began on what locals call Entrepreneurship Street, a modest stretch of shops and homestays entirely run by women. These weren’t symbolic storefronts for tourists; they were real enterprises managed with pride and precision. Handmade crafts, preserved foods, e-commerce shops, each woman I met was not only a business owner but also a storyteller, curator, and innovator.

Some had migrated back from cities, others had never left, but all of them shared a drive that was deeply rooted in what the community calls the “Qianhe Women’s Spirit” a tradition of equality and resilience that dates back to the revolutionary era.

Before I visited Qianhe Village in Jiande, Zhejiang Province, I had only a vague sense of what rural China might look like. I expected quiet lanes, hardworking farmers, and the slow pull of tradition. What I didn’t expect was to find myself in a place where women weren’t just participating in society, they were shaping it. Not as a matter of ideology or policy branding, but as a lived, daily truth.

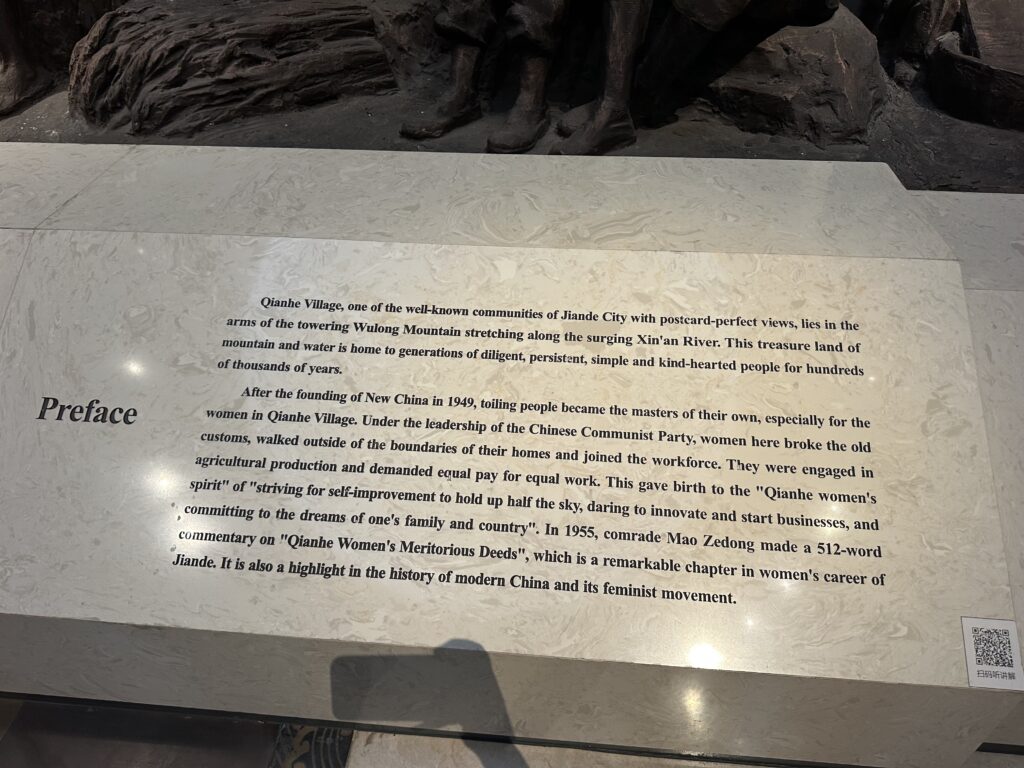

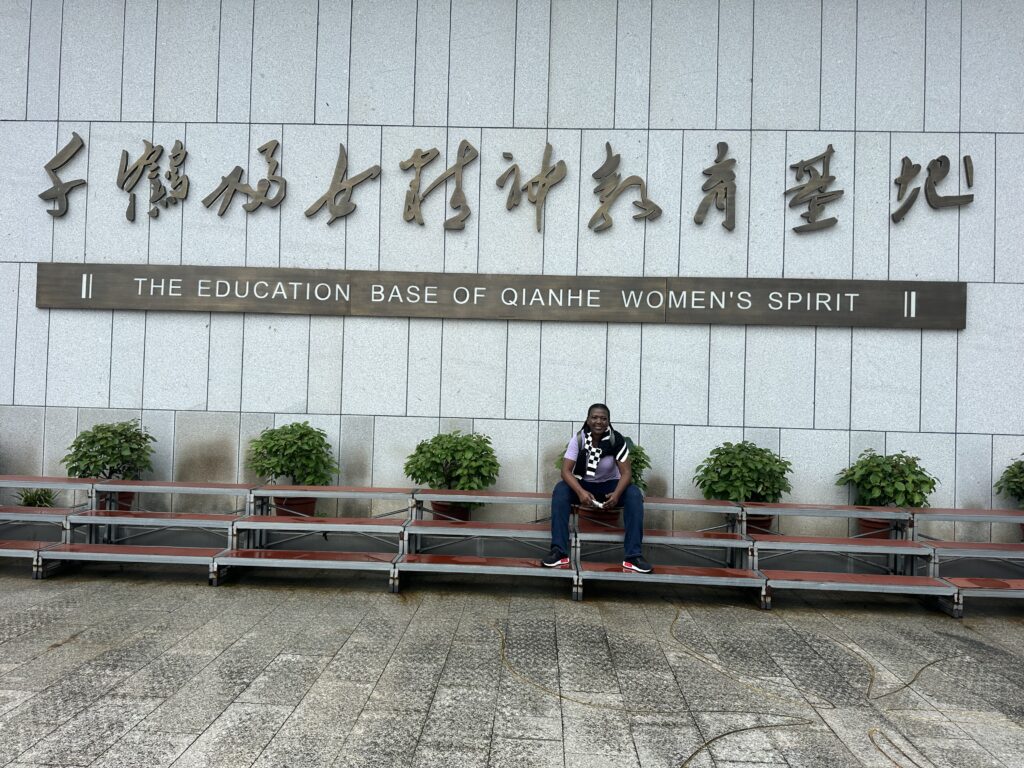

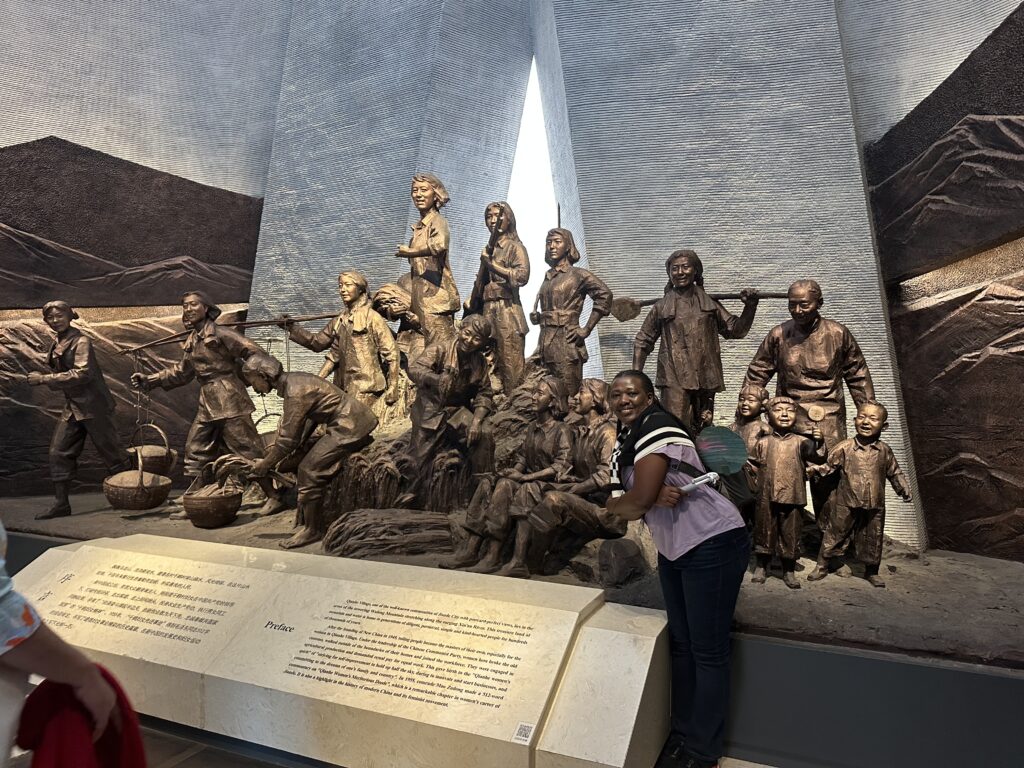

That legacy is no accident. Jiande holds a special place in China’s history as the birthplace of one of its most enduring slogans: “Women hold up half the sky.” Walking into Qianhe’s exhibition hall, lined with black-and-white portraits of women who trained as medics, fighters, and teachers in the 1950s, I felt the weight of that phrase shift from abstraction to reality. These were not propaganda icons. They were farmers and freedom fighters, matriarchs and mayors. And they hadn’t stopped building.

What moved me most was not the scale of the businesses but the intention behind them. These women weren’t simply generating income. They were creating dignity for themselves, for their families, and for their village. They were embedding modern entrepreneurship into the soil of tradition.

A young woman told me, “When tourists come here, I don’t just want them to spend money. I want them to understand what kind of people live here.” Her business was as much about preserving local culture as it was about profit.

This interweaving of legacy and leadership isn’t confined to Qianhe. Across Zhejiang Province, there is a concerted effort to ensure that women, particularly in rural areas are not left behind in China’s modernization.

The Zhejiang Women Cadre School in Hangzhou is one such example. On paper, it’s a training center. In practice, it’s a springboard. Women arrive from all corners of the province to study everything from early childhood development to digital marketing, rural governance, and social work. Some graduate with university degrees through a partnership with China Women’s University; others return to their towns as mayors, care workers, or digital entrepreneurs.

The school is not just producing workers, it is cultivating leaders. And critically, it is doing so with a focus on women from underserved regions who may never have had the chance to see themselves as decision-makers. Here, education is not a ladder out of the village. It is a bridge back into it, fortified with new tools and visions.

I saw this same ethos echoed in places like the Qiumei Women’s Common Prosperity Workshop in Datong Town, where women gather to learn marketable skills and run small cooperatives. In Jiuxian Park, women are driving rural green transformation, pioneering sustainable farming and ecological tourism.

At the Women’s Cloud Innovation Practice Base, also in Datong, rural women are learning to digitize services and promote household industries through online platforms. These are not token gestures. They are structural investments in women as economic and civic engines.

It would be easy to view all of this through the lens of policy success. Certainly, the state has played a role in directing resources toward women’s development. But what I saw and felt, was more profound. This was not top-down transformation, it was bottom-up conviction. These women were not waiting for campaigns to include them. They had long since made themselves essential.

In many Western narratives, rural China is painted as frozen in time conservative, male-dominated, resistant to change. My experience shattered that frame. In villages like Shanfeng and Genglou, I saw women doing the work of both continuity and disruption.

They were building businesses while tending to their elders, developing tourism while preserving dialects, running party branches while weaving local myths into the modern story of China.

“Empowerment” is too thin a word for what’s happening in these places. What I saw in Jiande was inheritance transformed into leadership. These women aren’t just holding up half the sky. They’re laying the foundations for a future that remembers its past without being limited by it.

If we want to understand what sustainable development truly looks like, we would do well to look not only to skyscrapers and tech parks, but to the quiet power being built woman by woman, village by village in the heart of rural China.

The phrase “Women hold up half the sky”, often attributed to Mao Zedong, finds its true origin not in Beijing, but in Qianhe Village itself. In the 1950s, as women in Qianhe stepped into roles as militia members, tractor drivers, and collective leaders during the early formation of New China, a local woman reportedly stood during a public meeting and declared, “Don’t we also hold up half the sky?” The phrase quickly gained traction, echoing across regional newspapers until it reached the Chairman himself.

Today, the Qianhe Women’s History Museum preserves this legacy through portraits, personal items, and stories of women who shaped village life alongside men, not just in revolution, but in rebuilding. Their legacy lives on in the daughters and granddaughters now running businesses on Entrepreneurship Street, proof that in Qianhe, the sky was always shared.