In many parts of the world, food is simply survival, a routine, a necessity, maybe an indulgence. But in China, I saw something far deeper. In Beijing’s alleyways, in Hangzhou’s old neighborhoods, and in the hills of Jiande, I came to understand that food here is custom, history, philosophy, and identity.

I arrived in China expecting sights, architecture, museums, and natural beauty. I got those, yes. But what stayed with me was what I tasted and what those tastes revealed. In China, food is not just what fills the stomach, it’s what nourishes the body, honors the land, and reflects generations of knowledge. It’s not a side note to life, it is life, expressed in bowls and steam and care.

In China, food isn’t hurried. It’s not dominated by convenience. Even in fast-paced Beijing, there was a kind of quiet honor in the cooking. Meals weren’t just prepared, they were considered.

But it wasn’t until I left the capital and traveled into Zhejiang province that I truly began to understand just how deeply food was woven into everyday life.

In Hangzhou, tea is everywhere, grown on hillsides, poured into tiny cups, served with a silence that feels more like respect than formality. The vegetables were bitter, clean, and bright, nothing like the sugar-heavy sauces I was used to at home. When I asked what was in the dish, the farmer simply said, “What the mountain gives.”

That mindset fascinated me. In China, they find food in what others might overlook: leaves, roots, sea creatures, insects, mountain herbs. If a plant isn’t poisonous, it’s considered food. And if it is poisonous, there’s a good chance it’s used as medicine. That’s not just a culinary approach, it’s a worldview. One that sees value in everything, and waste as something to be avoided not just practically, but morally.

In Jiande, a smaller city surrounded by forested hills, that relationship to food became even more vivid. What impressed me most was how carefully they cooked, not just for taste, but to preserve nutrients and match the body’s needs. Everything was balanced. Nothing overwhelmed. Meals gave energy without heaviness, warmth without excess. It made me question my own habits, where flavor often comes from salt, sugar, and shortcuts.

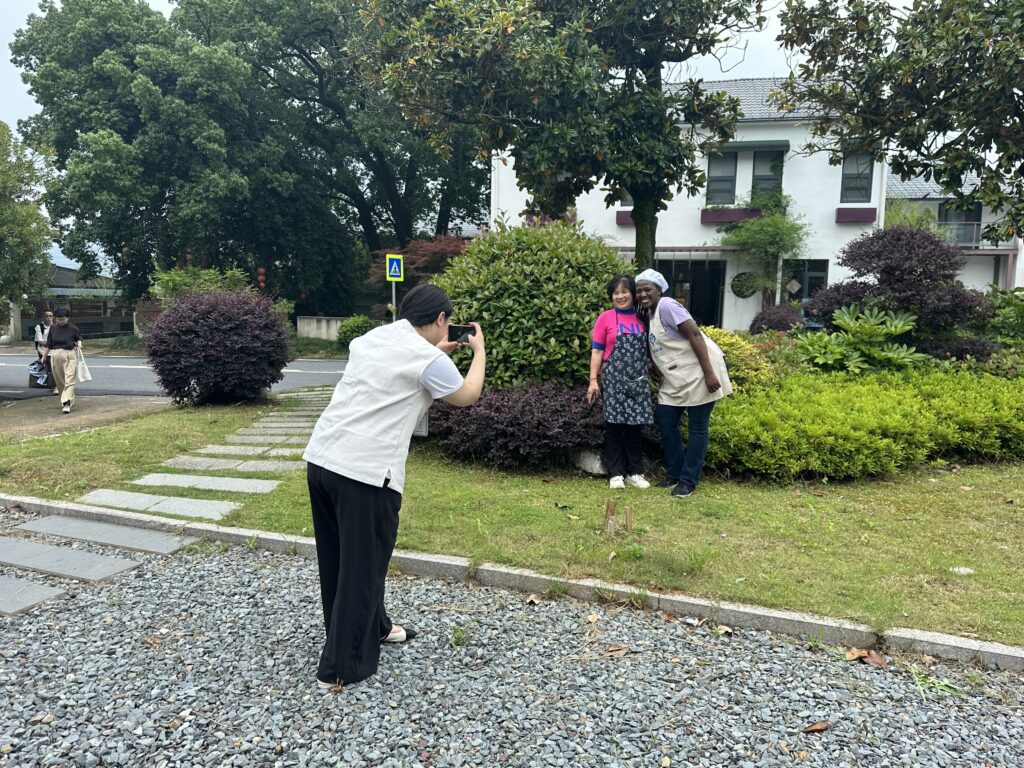

And this wisdom wasn’t trapped in the past, it was active, adaptable. In Jiande, I saw how locals are turning this culinary heritage into a way of life that welcomes the world. Families host travelers. Cooking classes are offered in small homes. Recipes are shared, not just for show, but because they carry pride, real pride, the kind that says, this is who we are, and you’re welcome to taste it.

Chinese cuisine, I realized, is a passport, a teacher, a business, and most of all, a treasured inheritance shared with care. Each dish is a narrative. Clay pot rice tells a story of patience. Pickled radishes speak of preservation, of seasons, of waiting. Even a dumpling can carry the shape of tradition in your hands.

I left China changed, not just in how I eat, but in how I think about what food means. It’s not just about feeding ourselves. It’s about remembering who we are, and how we live with the land, and with each other.

In China, food is not just what sustains life. It defines it.

In the hills and towns of Jiande, Zhejiang Province, I saw how deeply food, land, and tradition are intertwined. In a workshop called Rose, artisans transformed rose petals into everything from jams and candies to teas and skincare, turning a single flower into both nourishment and ritual.

In Xiaya and Lianhua towns, I walked through narrow streets where locals harvested herbs and wild greens from the surrounding mountains, blending culinary and medicinal uses with quiet mastery.

At the vast Ten-Thousand-Mu Xixiang tea plantation, the air smelled of fresh leaves and rain-soaked soil; the farmers there didn’t just grow tea, they lived it, speaking of its cooling properties and its role in daily health.

In Datong and Shouchang, I shared meals with families who served pickled vegetables, bamboo shoots, and foraged greens, ingredients gathered not for novelty, but because they belonged to the land and to their way of life.

Everywhere I went, nothing was wasted, and everything had a place. This wasn’t just cooking, it was continuity, passed down through kitchens and cups, season after season.