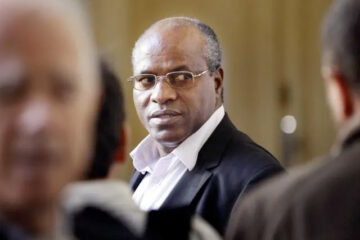

A Paris appeal court has upheld the 24-year prison sentence of Rwandan doctor Sosthène Munyemana for his role in the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, a ruling that renews debate over how far national courts can go in delivering justice for crimes committed beyond their borders.

The decision marks the end of a long legal journey for the former gynecologist, who fled Rwanda in 1994 and settled in France, where he worked in a hospital near Bordeaux for years before facing trial. His case is one of a series of landmark prosecutions that have tested both the capacity and the conscience of French justice in dealing with Rwanda’s darkest chapter.

A Long Path to Judgment

Dr. Munyemana was first convicted in December 2023 after a six-week trial in Paris. The court found him guilty of aiding and abetting genocide, participating in a criminal conspiracy to commit genocide, and depriving civilians of liberty leading to death. Testimonies from survivors and witnesses described how, in April and May 1994, Munyemana joined local officials and militia groups who rounded up Tutsi civilians in his commune and detained them under inhumane conditions.

Prosecutors alleged that Munyemana transformed a local administrative office into a detention site, where hundreds of Tutsis were held before being handed over to militias for execution. While the defendant denied any involvement, the court concluded that he used his authority and influence to facilitate the killings rather than prevent them.

His defense lawyers immediately appealed the decision, arguing that the court had misinterpreted witness statements and relied on “uncorroborated and time-faded memories.” But the Appeal Court in 2025 reaffirmed both the conviction and the 24-year sentence, finding the evidence consistent, credible, and legally sufficient.

“The appellate panel determined that no procedural error or miscarriage of justice occurred,” said a judicial source familiar with the verdict. “The original ruling stands in its entirety.”

A Trial of Memory and Law

The hearings in Paris revisited familiar challenges in cases tied to the Rwandan genocide: the erosion of memory, the difficulty of cross-continental evidence gathering, and the tension between national justice and international accountability.

Witnesses, many now living in Rwanda, testified via video link, describing Munyemana’s alleged involvement in organizing roadblocks, detaining Tutsi civilians, and helping local administrators draft lists of people to be targeted. The defense countered that these testimonies were shaped by trauma, distance, and the political pressures of time.

Observers from rights groups such as ‘Collectif des Parties Civiles pour le Rwanda’ (CPCR), which brought the civil suit, called the verdict “a confirmation of truth and perseverance.”

“This appeal judgment is more than symbolic,” said Alain Gauthier, co-founder of the CPCR. “It shows that impunity can be fought even 30 years later, and that justice can cross borders when humanity is at stake.”

France’s Legal Reach: Universal Jurisdiction in Action

Under French law, genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes fall under universal jurisdiction, allowing French courts to prosecute foreign nationals for acts committed abroad when no other competent jurisdiction is able or willing to do so. The legal framework derives from both the 1948 Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, integrated into French law in 1996 and 2010 respectively.

Munyemana’s trial, like those of Laurent Bucyibaruta (‘prefet’ of Gikongoro) and Octavien Ngenzi and Tite Barahira (mayors of Kabarondo), demonstrates how France has gradually accepted its judicial responsibility for suspects residing on its territory. The CPCR estimates that more than 40 cases of alleged Rwandan perpetrators remain under French investigation.

“France’s courts have become a secondary tribunal for the Rwandan genocide,” said legal scholar Marie-Aude Catala of the University of Lyon. “These trials are not political gestures but fulfill international obligations that stem from the Genocide Convention’s demand: to prosecute or extradite.”

A Sensitive Bilateral Context

Relations between Paris and Kigali have historically been strained by France’s perceived inaction during the 1994 genocide. While ties have improved in recent years, cases like Munyemana’s still carry political weight.

In Rwanda, survivor organizations such as Ibuka welcomed the Paris ruling, calling it “a long-overdue recognition of the international community’s duty to pursue justice.” However, others, including legal analysts in Kigali, noted that such verdicts arrive too late for many survivors who have passed away or lost faith in seeing justice served.

“Justice delayed is not always justice denied,” said Rwandan legal expert Béatrice Mukamana. “It still matters that the truth is written in legal history, even if time has dulled the pain.”

Appeal’s Limited Scope, Broader Significance

The 2025 appeal did not introduce new charges or witnesses; it was instead a judicial re-examination of existing evidence and procedure. French law allows full rehearing of facts in assize appeals, but in this case, the appellate court largely relied on the record from the first trial, finding no substantive grounds to modify the verdict.

While Munyemana’s legal team can seek a further review before France’s Court of Cassation on points of law, such an appeal would not question the facts, only the interpretation of them. For now, the doctor’s 24-year prison sentence stands as final and enforceable.

The Aftermath: Beyond the Courtroom

For Rwandans, the ruling resonates far beyond one man’s fate. It strengthens a growing sense that international justice mechanisms however delayed can reinforce national reconciliation. For French institutions, it underscores their continuing reckoning with a history once marked by hesitation to confront genocide-related responsibilities.

The ruling also joins a broader international conversation: what is the lifespan of justice?

Thirty years after the genocide, survivors continue to testify, new prosecutions emerge, and national courts like France’s play a crucial role in bridging the distance between atrocity and accountability.

Legal and Moral Legacy

The Paris appeal court’s decision may close the legal chapter on Dr. Munyemana, but it reopens the moral one about complicity, responsibility, and remembrance.

As one survivor who testified in the case told Le Monde:

“It was not vengeance we wanted, only truth. The truth that even a doctor can kill when humanity falls apart.”

For Rwanda and for France, that truth now confirmed by a court of appeal stands as both warning and lesson: that justice may come late, but it still comes, and that memory, when tested by time, can still speak with the clarity of law.