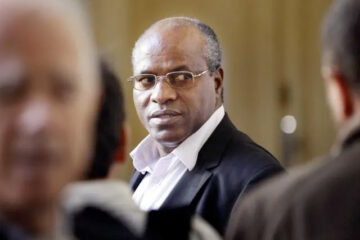

In the solemn quiet of the courtroom, time seemed to fold upon itself. Before the judges sat Dr. Sosthène Munyemana, once among Rwanda’s few gynecologists, now standing trial in France on charges of genocide, crimes against humanity, and participation in a group formed to prepare those crimes.

Across three intense sessions, his interrogation revealed a man caught between memory and accusation, a figure oscillating between professional pride, political naïveté, and the unbearable weight of Rwanda’s history.

A Man between Two Realities

The hearings opened with procedural exchanges before turning to Munyemana’s psychological assessments reports he sharply disputed. He accused the expert of misunderstanding his grief and culture, recalling that he had just lost his mother at the time. “She reduced my parents to monsters, and me to an abused child,” he told the court, calling the evaluation “unfair and detached from Rwandan reality.”

Calm yet defensive, Munyemana described himself as a doctor trapped by events beyond his control. “We were only five gynecologists in Rwanda,” he said. “I was known, yes, but that never meant power.”

He recounted his work at Butare hospital during the genocide treating patients “of all ethnicities” in an atmosphere of fear and flight. “After four o’clock, the hospital was empty,” he said. “People walked with their heads down.” He denied any involvement in ethnic persecution, citing the case of Beata Uwamariya, a Tutsi woman he helped deliver safely before soldiers began raiding wards. “I sent her home to protect her life,” he said quietly. “I never spoke a single anti-Tutsi word.”

The Weight of Politics

The court then examined his political past. A member of the ‘Mouvement Démocratique Républicain’ (MDR), Munyemana presented himself as a moderate drawn to the party’s opposition to ethnic division. Yet the MDR would fracture under pressure, between radicals seeking power and leaders trying to survive. “Politics became chaos,” he said.

Judges questioned him about a “motion” broadcast on Rwandan radio in April 1994, a document signed by Butare intellectuals, including Munyemana, praising the national army and avoiding mention of Tutsi victims. The text has long been seen as lending legitimacy to the interim government that organized the massacres.

Munyemana claimed the letter was never meant for domestic propaganda. “It was intended for the United Nations,” he explained. “We wanted to warn them not to withdraw peacekeepers. The version read on the radio was not ours.” Pressed on why the letter’s tone appeared supportive of the military, he replied, “We were four writing it; it was a compromise.”

The Fragile Boundary between Fear and Complicity

The questioning then turned local to Tumba, the hillside community where Munyemana lived and worked. Witnesses accused him of participating in meetings that organized night patrols and barriers later used to identify and kill Tutsi civilians. Munyemana acknowledged attending a community meeting on 17 April 1994 but insisted that his role was defensive. “We wanted to protect the area from chaos,” he said. “Our patrols were mixed, Hutu and Tutsi together, and we had nothing but sticks.”

Prosecutors challenged the logic: “You claim to protect people while they are being slaughtered in daylight,” one judge noted. Munyemana replied, “Our efforts were weak. Perhaps they were only symbolic, but it made us feel we were doing something.”

He denied ordering or maintaining roadblocks and said that when the patrols turned violent, he felt powerless to stop them. “Everyone was afraid,” he said. “Silence was the only way to survive.”

The Turning Point in Butare

The testimony returned to 19 April 1994, when Butare’s ‘prefet’, Jean-Baptiste Habyarimana, was dismissed by the interim government, a moment historians see as the spark for the massacres in the region. “It was a catastrophe,” said Munyemana. “That day, everything changed.”

He admitted hearing the inflammatory speech delivered that same day by interim president Théodore Sindukubwabo, once his medical professor. “It was clearly a call to kill,” he acknowledged. Yet he stayed. “I had three children, no car, and nowhere to go,” he said. “Leaving was impossible.”

Between Denial and Accountability

Throughout his interrogation, Munyemana maintained a delicate balance, rejecting guilt while admitting moral paralysis. His words traced the outline of a man who neither acted as a killer nor as a rescuer, caught in the murky space between inaction and complicity.

For the French court, the case is part of a broader reckoning: the pursuit of alleged perpetrators who found refuge in France after 1994. Munyemana’s trial three decades after the genocide that killed more than 1,000,000 people probes not only one man’s past but the deeper question of how justice can measure silence, fear, and the limits of human courage.

As the hearings concluded, the judges were left with a story of blurred boundaries between healer and citizen, witness and participant, memory and denial. Whether Dr. Sosthène Munyemana was an accomplice or simply overwhelmed by the tide of history now rests with the court’s judgment and with Rwanda’s enduring demand for truth.