When 12-year-old Jean Bosco Kageruka, a primary school pupil in Nyagatare District, began complaining of stomach pains and blood in his urine, his parents thought it was malaria. However, tests at the local health center revealed another culprit: schistosomiasis, locally known as bilharzia.

“I didn’t know children could get such a disease just from playing in water,” says his mother, Florence Uwimana, who fetches water daily from Lake Muhazi. “We always thought the lake was safe. Now we are more careful.”

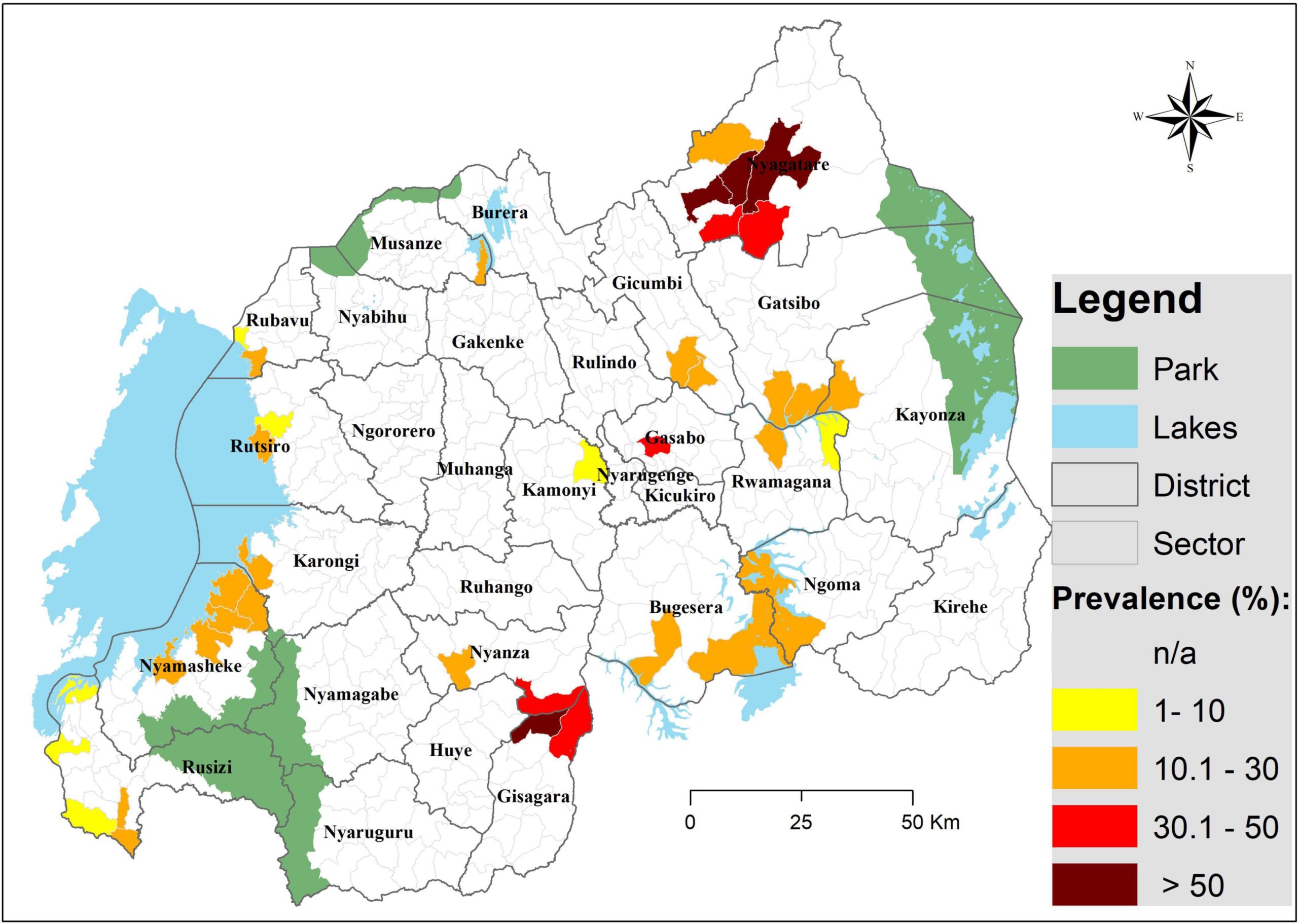

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by worms that live in freshwater. Infection happens when skin encounters water contaminated by the parasites. According to the Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC), the disease is endemic in districts bordering major lakes and rivers, especially Nyagatare, Kirehe, Gisagara, and Bugesera.

“Our mapping shows that between 15% and 40% of people in high-risk areas are infected,” explains Dr. Sabin Nsanzimana, Minister of Health. “Children are the most vulnerable because they often swim, fetch water, or help their families with household chores near open water.”

The government, with support from partners like the World Health Organization (WHO), has rolled out annual mass drug administration campaigns, particularly in schools. In 2023 alone, more than 6 million Rwandans received preventive treatment for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths, according to official RBC data.

However, prevention remains a challenge. Dr. Mbituyumuremyi, Head of Malaria and NTDs at RBC, notes that behavioral change is as important as medicine.

“You cannot treat your way out of schistosomiasis. Without safe water, sanitation, and health education, new infections keep happening. That’s why WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) interventions are critical.”

At the community level, teachers and local leaders are stepping in. In Gisagara District, Headteacher Emmanuel Habimana of Gikonko Primary School runs awareness sessions before classes.

“We show children pictures of snails that carry the disease and explain why they must avoid swimming in ponds. Many parents thank us because they too did not know.”

Health experts warn that the impact of bilharzia goes beyond stomachaches. Untreated, it can cause liver and kidney damage, infertility, and increased vulnerability to other infections. For children, chronic infections lead to anemia and poor school performance.

Rwanda’s fight against schistosomiasis has been hailed internationally as a success story in community-based health delivery. However, challenges remain in reaching remote communities and maintaining consistent behavior change.

Uwimana, Kageruka’s mother, says that the experience changed how her family lives.

“Now we only fetch water from the borehole, even if it means walking longer. My son is better after treatment, but I don’t want to see him sick again.”

As Rwanda moves toward eliminating neglected tropical diseases by 2030, experts say schistosomiasis is both a medical and social issue. Sustained investment in health education, infrastructure, and community engagement will decide whether children like Kageruka grow up free from the silent burden of bilharzia.