Efforts to bring peace to the troubled eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have gained international attention this month, with two separate diplomatic agreements signed within weeks, one in Washington under U.S. mediation, the other in Doha with Qatari backing.

Yet while the ink dries on peace deals, tensions over the DRC’s vast mineral wealth continue to simmer, raising questions about whose interests are truly being served.

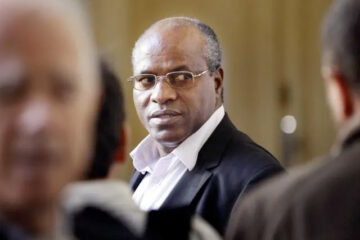

According to writer and financial analyst Junior Mbuyi, these agreements expose a troubling pattern: “Central Africa is not in control of its own peace process,” he says. “Foreign powers continue to dominate both diplomacy and development in the region.”

The two treaties reveal stark contrasts in approach. The Doha agreement directly acknowledges the presence of the M23 rebel group, a key player in ongoing violence, while the Washington accord makes no mention of them. Mbuyi interprets this as a deliberate distinction: “The American strategy is economic and image-focused, whereas Qatar is trying to bring everyone to the table even if discreetly.”

Behind the diplomatic dance lies a deeper race for control of the DRC’s natural resources. Home to some of the world’s largest reserves of cobalt and lithium, the country is becoming a strategic battleground for clean energy minerals.

In Tanganyika province, this struggle has turned legal. The Congolese government recently suspended Australian firm AVZ Minerals’ license for the massive Manono lithium project, prompting the company to seek international arbitration. Yet, in a surprise move on July 18, Kinshasa signed a memorandum of understanding with U.S.-based KoBold Metals to develop part of the same site known as Roche Dure.

KoBold, backed by prominent U.S. investors and tech giants, has been presented as a future cornerstone of the lithium supply chain. But AVZ, which holds the majority stake in the project through its subsidiary Dathcom, claims the deal violates a January ruling by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. That ruling instructed the DRC to recognize Dathcom’s rights and preserve its access during ongoing proceedings.

This legal grey zone is emblematic of what Mbuyi calls a “fragile sovereignty over national assets.” He argues that beyond diplomatic mediation, the DRC needs a decisive internal strategy.

“The country must review and renegotiate its mining contracts. Without reforms, these peace agreements risk becoming smokescreens for resource extraction under foreign control,” Mbuyi warns.

He calls for a national mining code overhaul, increased transparency, and the renegotiation of current partnerships. For him, true peace is inseparable from economic justice.

As international actors position themselves around the DRC’s lithium and cobalt, one thing is clear: while peace may be written on paper, the future of the country’s wealth and who benefits from it remains highly contested.