Africa needs an estimated 1.3 trillion USD each year to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but current global financing systems are failing the continent, African leaders declared at the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) held in Seville, Spain.

At the close of the high-level meeting, participants adopted a 38-page “Seville Commitment” a set of voluntary measures aimed at improving financial access and aligning investments with sustainable development. African delegates pushed for bolder reforms, warning that without urgent changes, development goals and regional initiatives like AfCFTA and Agenda 2063 remain out of reach.

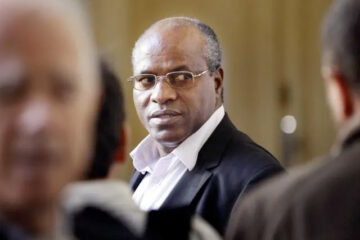

“For Africa, this is not a theoretical discussion,” said Claver Gatete, UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA). “It’s a matter of survival, transformation, and sovereignty over our development trajectory.”

Despite a growing pool of viable projects in energy, transport, agriculture, and digital infrastructure, only two African nations enjoy investment-grade credit ratings. High borrowing costs, shrinking access to concessional loans, and outdated risk assessments continue to stifle investment and leave countries especially middle-income ones trapped in a financing limbo.

The ECA called for sweeping reforms, including the creation of an African credit rating agency, updates to debt qualification criteria, and the integration of multidimensional vulnerability indices to better reflect the social and structural challenges that GDP alone cannot measure.

One of Africa’s headline proposals at the conference was the launch of the Platform for Action on Private Investment Mobilization. Spearheaded by ECA in partnership with Convergence Blended Finance, OECD-DAC, and others, the initiative aims to unlock private capital through blended finance and direct it toward Africa’s strategic priorities, renewable energy, industrial zones, and trade corridors among them.

“We are not proposing another list of projects,” Gatete explained. “We are proposing a coordinated, African-led mechanism to shift capital to where it’s most needed.”

With the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) creating a $3.4 trillion economic bloc of 1.5 billion people, ECA underscored that Africa’s challenge is not opportunity but perception. Risk-averse investment behavior and flawed credit rating models continue to deter capital, despite ongoing reforms on the ground.

African countries also advocated for faster and fairer debt restructuring, particularly involving private creditors and middle-income nations excluded from concessional terms but burdened by social vulnerabilities. The ECA promoted innovative tools such as debt-for-climate swaps and transition bonds, and called for sustainability to be built into debt sustainability frameworks.

The Seville Commitment recognized many of these proposals, supporting expanded use of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), improved debt transparency, and more inclusive sovereign debt frameworks.

To ensure accountability and progress tracking, the ECA proposed an Integrated Follow-Up System, supported by regional observatories and country-level coordination units, to be co-led in Africa by the African Union Commission, ECA, and the African Development Bank.

“Without mechanisms to track what we finance, and how, we risk eroding credibility,” Gatete warned. “Accountability systems must be grounded in data and driven by national priorities.”

As the dust settles in Seville, one thing is clear: Africa is not just asking for support, it is demanding a financial architecture that reflects its realities, ambitions, and growing economic potential.